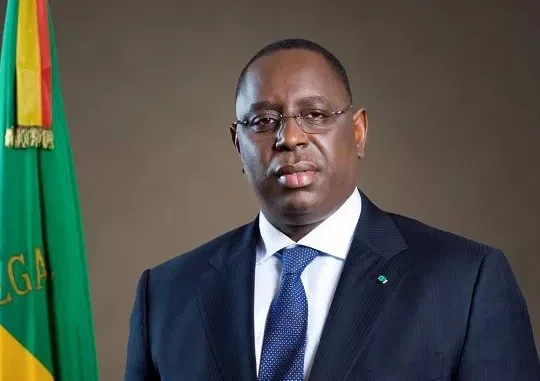

Democracy activists in Senegal and Mozambique are sounding the alarm over presidents Macky Sall and Filipe Nyusi’s refusal to rule out running for third terms. Local opposition to third terms is not surprising. Third terms are deeply unpopular with most everyone in Africa except for the handful of men – and so far, they are all men – who decide to seek them.

According to Afrobarometer, three-quarters of respondents in 34 African countries consistently support holding their presidents to two terms in office. Third terms also do real damage. Joseph Siegle and Candace Cook report a nearly 50-place differential in ranking on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index between countries that have respected term limits and those which have not. Siegle and Cook also found that countries with term-limit violations are more conflict prone and earn a median score of 22/100 on Freedom House’s Global Freedom Index as compared to a median score of 69/100 for countries where term limits have been respected.

Removing term limits also short-circuits democracy by creating Presidents-for-Life. Only two presidents in Africa – Sam Nujoma in Namibia (2005) and José Eduardo dos Santos in Angola (2017) – have retired willingly after sidestepping term limits to secure third terms. With the exception of Senegal’s Abdou Diouf and Abdoulaye Wade, whose third term bids were rejected by voters, everyone else who violated term limits in sub-Saharan Africa either died in office, was overthrown, or is still in power today. Three of the four who died in office (Bongo, Eyadema, and Deby) were replaced by their sons and one of these (Faure Gnassingbe in Togo) already rolled back term limits after they were restored following his father’s death. The nine term-limit violators now in office (see Table 1) share more than 230 years in power between them, and not one – including Cameroon’s Paul Biya who is 90 years old and in poor health – shows any sign of retirement.

It is also important to note that third term bids inflict damage regardless of outcome simply by denying an opportunity to establish precedent. Diouf and Wade, for instance, failed to win third terms but succeeded in preventing Senegal from joining the list of African nations with a precedent for respecting term limits. The absence of this precedent is now reverberating through the streets of Dakar today. The same holds for Blaise Compaore in Burkina Faso. While Compaore’s second attempt at a “third” term bid in 2014 ended in his ouster (he had already removed term limits once only to restore them again later), he succeeded in something equally insidious and far-reaching: preventing Burkina Faso from establishing a precedent for respecting term limits. For the Burkinabe, who are now under military rule, the next chance to establish this precedent may not come around again for another generation. In Senegal, on the other hand, the time to create this precedent is now. Senegal’s democracy is one of the strongest in Africa but popular sentiment may boil over if yet another Senegalese president instrumentalizes the courts to hobble opponents and pave the way for a third term bid in 2024.

President Nyusi’s refusal to rule out a third term in Mozambique is equally consequential, but for a slightly different reason. Nineteen countries in Africa have established a precedent for respecting term limits (Table 2). In all but one, this precedent still holds. The only outlier is Mali which has suffered three miliary coups since Alpha Oumar Konare termed out in 2002. This means that of the 36 presidential transitions that have occurred in African countries after establishing a precedent for respecting term limits, all but three transitions in Mali – or 92% in total – have been constitutional. This is a remarkable number, particularly for a continent so often portrayed as coup prone.

But there is more. Not a single president in an African country where term limits have been respected has attempted to roll back this precedent by running for a third term. Some have toyed with the idea as Nyusi is now doing in Mozambique but no one has actually done it – yet. Nothing in African politics is certain except, it would seem, this: every president in an African country with a precedent for respecting term limits has abided by this precedent. Posner and Young alluded to this several years ago. “One of the strongest predictors of a leader’s decision about whether or not to try for a third term,” they observed, “is whether his predecessor(s) voluntarily gave up power when they faced term limits of their own.” Posner and Young concluded that in instances “where a predecessor had stepped down in the face of two-term limit, every single president who followed chose not to push for a third term.” During the time-frame Posner and Young studied, from 1990 to 2015, this standard applied to ten cases. There are fifteen cases now and the precedent still holds. Nyusi will be either the 16th president to abide by this precedent or the first to break it.

If Nyusi were to seek a third term, it would constitute more than a major setback for democracy in Mozambique; it would break a continent-wide precedent that has held for nearly 20 years, potentially opening the floodgates for other African presidents in countries with precedents for respecting term limits to do the same. Precedents in Africa matter. They are powerful. And continental leaders watch closely what their fellow colleagues are able to get away with. Failing to create a new precedent in Dakar, or rolling back an already established one in Maputo, will damage democracy not only in Senegal and Mozambique but across Africa.

*For relevant tables on ‘Term Limit Evasion in Sub-Saharan Africa (1990 – 2023)’ and ‘Presidential Successions Following Application of Term Limits in Africa (1990 to 2023),’ see African Arguments.

The author, Aaron Sampson, is a U.S. federal employee. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Government.